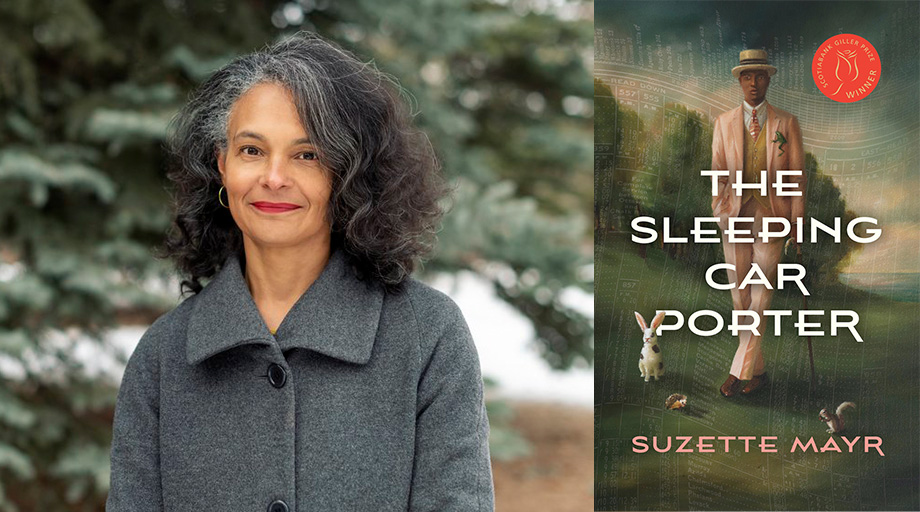

Dr. Suzette Mayr is the author of six novels, including her most recent book The Sleeping Car Porter, winner of the 2022 Scotiabank Giller Prize and shortlisted for many prestigious awards. She is a Professor at the University of Calgary who teaches creative writing in the Department of English, and a Killam Laureate.

Researched and written over a period of nearly 20 years, The Sleeping Car Porter follows Baxter, a queer Black sleeping car porter in 1929. On a cross-country train ride out west that gets stalled for two extra days in the Rocky Mountains, Baxter must contend with a trail full of unruly passengers, and his own sleep-deprived hallucinations and secret desires.

We spoke with Mayr about the research she did for this novel, and how the Chung Collection at UBC Library’s Open Collections helped shape its course.

Q: What was your research-to-writing process like for The Sleeping Car Porter?

For every book I’ve written, I’ve had to do research of some kind. With a book like Dr. Edith Vane and the Hares of Crawley Hall, which was my last book, I researched campus novels: who’s written what? What kinds of characters feature in campus novels? What are the conventions of the genre, and what was I going to do with that genre?

With this book, The Sleeping Car Porter, it was a much different process. Because it was historical fiction—and I had never written historical fiction before—I was really nervous about getting the details right. I also did not have a ton of confidence at the beginning.

“Throughout the research process, what I was missing was an actual timetable. What were the actual routes porters took? I was always looking for these timetables.”

When I started at the University of Calgary at my job [in 2003], I got a bit of seed funding to do research, so I went to New York and went to the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Over the years, as I became more involved in this project, I started reading history books. I found actually very little when it came to sleeping porters in Canadian terms of information about the minutiae, the very specific details of the job, like how much money is a “good” tip? How much is a “bad” tip? When the nonfiction history books talked about the job, they talked about it in very general terms.

I realized that I was making a huge mistake by restricting myself to Canadian history, because so much had been written on American porter history… so I started branching out. And as I went, I realized more and more that I needed to get into the nitty gritty. I was lucky enough to get a Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council Insight Grant [in 2013] so that I could visit physical archives.

I went to Vancouver and looked at the City of Vancouver Archives, and Ottawa at the National Library there, and in Montreal I went to Exporail. I went to Chicago. The Pullman archives in Winnipeg. In Cranbrook, there is a perfectly restored sleeping car and dining car from 1929. [The archivists there] also gave me access to a sleeping car porter uniform jacket.

For many years, it was me doing historical world-building. It wasn’t until I found, just by accident, a CBC article that talked about a VIA rail train that was stuck in the Rocky Mountains for 45 hours—that I realized that’s my story. So it was a very long and circuitous process.

Q: How did you discover the Chung Collection?

Throughout the research process, what I was missing was an actual timetable. What were the actual routes porters took? I was always looking for these timetables.

In March 2020, the pandemic was declared and I could not visit physical archives anymore. So I started desperately searching [online] for timetables from 1910 to 1930.

When I first started writing the book [in 2003], very little was digitized. It didn’t occur to me that over the 20 years that I was writing the book, that maybe some materials would become digitized. Then I came across this page [in the Chung Collection] and this was brilliant—this is was exactly what I wanted! And I loved how I could search it.

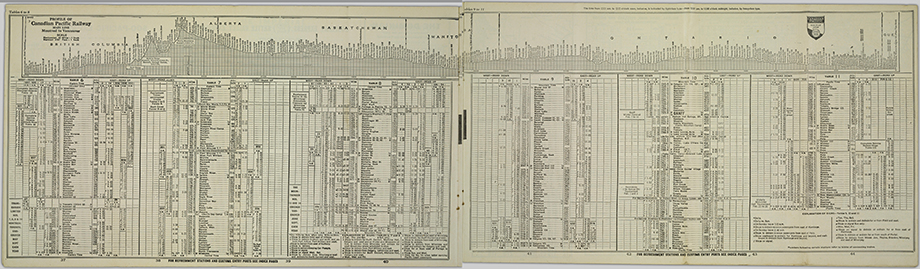

Image: Canadian Pacific Railway timetables, 18-19. From the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung at UBC Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections.

Q: Which sources from UBC Library’s Chung Collection did you use in your research?

[The timetable I found] was cross-Canada, Montreal to Vancouver, which is exactly what I wanted. It showed the elevations and gave me a rough sense of how long would it take to get from one point to the other. Admittedly, I don’t think this was the express train, but it still helped a lot because I was structuring my book based on where the train was in the country at a given time.

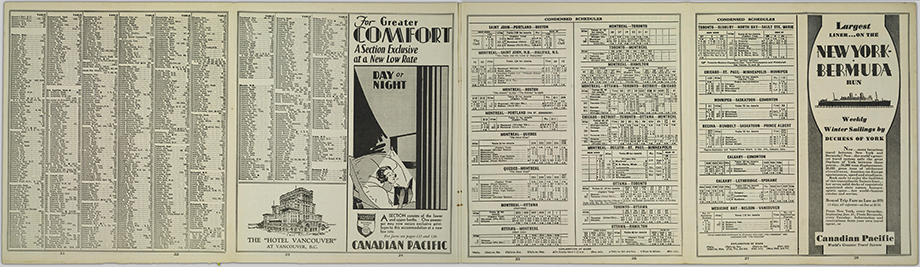

Image: Canadian Pacific Railway timetables, 14-15. From the Wallace B. Chung and Madeline H. Chung at UBC Library’s Rare Books and Special Collections.

I loved the tiny details, like at the bottom [where it lists] the refreshment stations and custom entry ports. That language was so valuable.

What was also hugely valuable as well was a page like this, that had the ads in it. I love this part here with the woman reading in her berth, and this ad for the Hotel Vancouver. Small details like that were massively important.

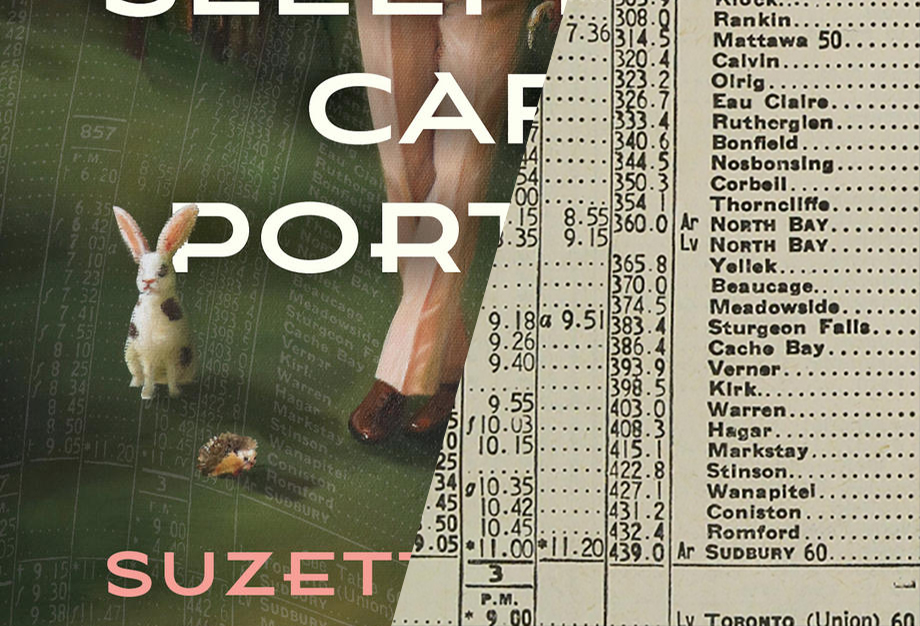

On the cover of the book, there’s that beautiful painting by Janet Hill, and there’s also an overlay which is taken from one of the timetables in the Chung collection.

Even though I wasn’t able to touch these materials, it was fabulous to just be able to zoom in and get these really nitty gritty details, and see the [station] names like Gogama and Agate. I found the names extremely poetic and they helped inform the opening section of the book where the character’s train is passing through all of these Ontario towns I had never heard of.

It was a lifesaver during the pandemic. And in the end, it was the best resource I could have found. I don’t think I would have been able to find these materials in the other physical archives, because archives are arranged in a way where the person who put it together isn’t necessarily interested in the same things that I am as a researcher. I want the ads. I want all the details. I want to see the texture of the paper. I love that tangibility, that tactility, it’s beautiful.

Image: Within the cover art of The Sleeping Car Porter, the textual overlay is taken from one of the timetables in the Chung collection.

Q: Is there anything that you learned from your research or writing process that you would want to do differently in a future project?

If I ever write another fiction that is historical, I’ll know right away to go read the fiction that was written in the era, because it’s much different from the fiction written about the era, or history books written about the era.

Talk to archivists, because they know what they’re talking about. Go to media from the era: newspapers, catalogs, that kind of material. And also just be open to falling down rabbit holes where you think you’re looking for one thing, but actually discover all of these other seemingly tangential details in the meantime. Don’t be afraid to follow those, and don’t think that they’re going to detract from your creativity.

The other really valuable lesson I learned was that you can do all the research in the world, but at a certain point, if you’re writing a historical fiction, you’re going to have to break the rules in order to write your story. I put a qualifying note in the book about how, sometimes in order to get at the truth of the book, a bit of reality has to fall by the wayside. Know what rules you’re breaking, but don’t be afraid to break those rules.

Q: What are you reading right now?

I’m reading The Taste of Hunger by Barbara Joan Scott. I’ve just started it. She’s a local writer, and so I’m looking forward to that! And I’m halfway through Mariana Enriquez’s Our Share of Night.

Borrow The Sleeping Car Porter from UBC Library.

Follow Mayr’s writing at suzettemayr.com